Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal Cancer

Multidisciplinary discussion on Colorectal Cancer

Listen as doctors from multiple disciplines discuss treatment options for patients with colorectal cancer.

Colorectal

Introduction

When cancer occurs in the colon or rectum, it is called colorectal cancer (CRC). It is also sometimes called bowel cancer. The colon and rectum (colorectum), along with the anus, make up the large intestine, which is sometimes also referred to as the large bowel.

The colon is divided into four sections.

- The ascending colon is on the right side of the body and is the first section of the large bowel where undigested food is received from the small intestine.

- The transverse colon crosses the abdomen from the right to the left. The combination of the ascending and transverse colon is referred to as the proximal or right colon.

- The descending colon is on the left side of the body.

- The sigmoid colon (shaped like an S”) is the last section of the colon and empties into the rectum. The combination of the descending and sigmoid colons is also called the distal or left colon.

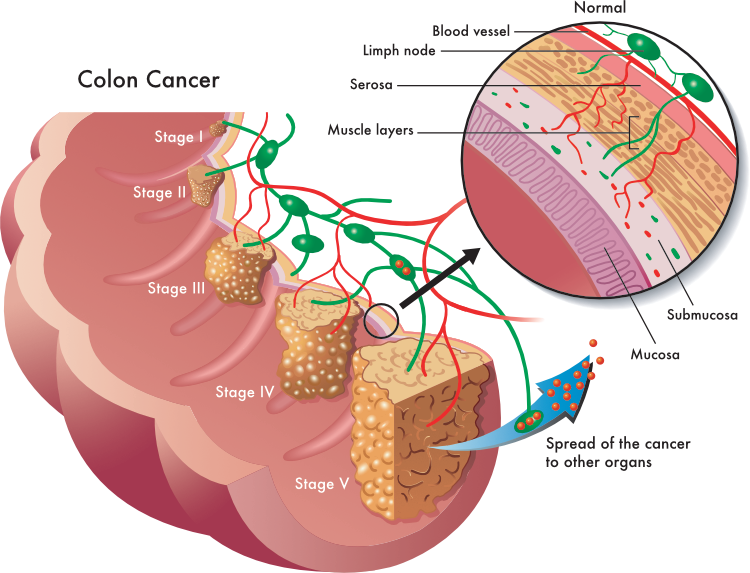

Stages of Colorectal panel (CRC)

CRC is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States. In 2022, an estimated 151,000 patients will be diagnosed with CRC in the United States with approximately 53,000 patients previously diagnosed with CRC will die of the disease. The 5-year relative survival rate for CRC is 65.3% and 58.4% at 10 years.2

The most important predictor of survival from CRC is the stage of the cancer at diagnosis with localized cancer having a better survival than patients diagnosed after the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or metastasized.2

CRC almost always begins as a polyp. A polyp is made up of abnormally growing cells location in the mucosal layer (inner lining) of the colon. These cells can be malignant (cancerous) or have the potential to become malignant. A polyp can be a flat bump (sessile) or shaped like a mushroom with a bulbous growth projecting from a stalk (pedunculated).

Having polyps is very common and are detected in about half of individuals over 50 who undergo a colonoscopy. They become more prevalent with age and are more common in men compared to women.3 Fortunately, fewer than 10% of polyps progress to become invasive cancer. The process occurs slowly over 10 to 20 years and as polyps increase in size.7-8

Approximately 20% to 34% of patients will have metastatic colorectal cancer when diagnosed and 50% to 60% of patients diagnosed with non-metastatic disease will develop colorectal metastases over time.9 Metastatic disease most often develops more than 6 months after local or regional treatment with the liver being the most common site.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person’s chance of developing cancer. While risk factors do not directly cause colorectal cancer, they can increase the likelihood that that cancer will occur. Some risk factors can be modified by life-style changes, while others cannot, like age. The following are examples of risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer.

Examples of lifestyle-related risk factors

Being overweight or obese – being overweight increases the risk of CRC. Compared to individuals who are normal weight, obese men have about a 50% higher risk of colon cancer and a 25% higher risk of rectal cancer. Obese women have about a 10% increased risk of colon cancer and no increased risk of rectal cancer.

Diet – what an individual eats can also influence the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Eating red meat and processed meat has been shown to increase the risk of developing CRC.

- Calcium consumption, either from dairy products or supplements decreases the risk of developing CRC.

- Eating whole grain food products has been shown to decrease the risk of CRC.

Smoking – Smokers are at increased risk of developing CRC.

Age – the risk of colorectal cancer increases as people get older with the majority of colorectal cancers occurring in individuals over 50 years of age. The average age when colon cancer is diagnosed is 68 years for men and 72 years for women. For rectal cancer, the average age at diagnosis is 63 years for both men and women.

Gender – Men have a slightly higher risk of developing CRC than women.

Race – black individuals have the highest rates of non-hereditary CRC and are more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age.

Family history of colorectal cancer – CRC can run in families with an increased risk if an immediate family member or other relative have had CRC. If an individual has a family history of colorectal cancer, their risk of developing the disease is nearly double. This risk increases if the family member was diagnosed with CRC before the age of 60. About 5% of cases of CRC are associated with inherited genetic mutation. This increases the risk of developing cancer and can also impact how the cancer is treated.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – individuals was IBD (e.g., ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease) can develop a chronic inflammation of the large intestine which in turn increases the risk of CRC.

Click here for more detailed information on risk factors associated with the development of CRC.

Treatment

Treatment for CRC is typically based on the stage of the cancer, the goal of the treatment, the size and location of the tumor(s), results from genetic testing and patient lifestyle factors.

Examples of possible goals for treatment include:

- Pursuing a curative treatment to eliminate the cancer.

- Shrinking the tumor to increase the ability to remove the tumor surgically.

- Slow the growth or progression of the cancer.

- Preventing the recurrence of the cancer.

- Implementing palliative (supportive) care to improve quality of life by relieving pain or avoiding/managing side effects caused by cancer treatment or discomfort when the individual elects to not undergo treatment.

Potential treatments can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and/or interventional procedures to directly treat the tumor. Detailed information on each of these options can be found in the modules listed below.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022 Jan;72(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708.

- SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics [Internet]. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Cited 2022 December 26].

- Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Variation of Adenoma Prevalence by Age, Sex, Race, and Colon Location in a Large Population: Implications for Screening and Quality Programs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(2):172-180.

- Levine JS, Ahnen DJ. Clinical practice. Adenomatous polyps of the colon. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2551-2557.

- Risio M. The natural history of adenomas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(3):271-280.

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary

target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12(1):1-9, - Stryker SJ, Wolff BG, Culp CE, Libbe SD, Ilstrup DM, MacCarty RL. Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1987;93(5):1009-1013.

- Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Pooler BD, et al. Assessment of volumetric growth rates of small colorectal polyps with CT colonography: a longitudinal study of natural history. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):711-720.

- Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(3):329-359. Published 2021 Mar 2. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012