CRC Chemotherapy

CRC Chemotherapy

Colorectal

Chemotherapy

While surgery is the primary treatment option for most patients with colorectal cancer, chemotherapy and the use of other newer drugs can also have an important role in the management of the disease. Chemotherapeutic drugs work by interrupting the growth and replication of cancer cells, with some being given during a specific stage of the cell cycle to increase their effectiveness.

Chemotherapy can be used alone or in combination with radiation as neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery in order to shrink the tumor to enable easier removal, as adjuvant therapy after surgery to treat residual cancer cells which may not have been removed in order to prevent disease recurrence, and long-term therapy to prevent metastases. The choice of which drug regimen to use is dependent on the stage of cancer the patient has and other factors which may impact their effectiveness or the likelihood of side effects.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is standard for patients with stage III disease and sometimes in stage II disease in selected patients with risk factors for recurrence.1 Chemotherapy rather than surgery has been the standard management for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with targeted biologic agents having a significant role in treatment with treatment more often being guided by the results of genetic testing of the tumor.1

How chemotherapy drugs work

There are several different classes of chemotherapy drugs which are used to treat colorectal cancer some of which are given orally and others intravenously. This includes:

- Antimetabolites – are “cytotoxic” drug that kill cells by mimicking molecules that a cell needs to grow. When cancer cells incorporate the chemical in these drugs, they are unable to replicate.

- Alkylating agents – are antineoplastic (anticancer) drugs which inhibit the transcription of DNA into RNA and prevents protein synthesis resulting in the inabilty for cancer cells to growing.

- Topoisomerase inhibitors – are a subclass of plant alkaloids that interfere with enzymes called topoisomerases. Topoisomerases enable strands of DNA to separate and be copied. Topoisomerase inhibitors prevent these enzymes from working resulting in the inability of cells to divide and replicate.

Chemotherapy drugs commonly used for colorectal cancer

- Fluorouracil (5-FU) – an antimetabolite

- Capecitabine – an oral form of 5-FU

- Leucovorin (folinic acid)- a vitamin that improves the effectiveness of 5-FU

- Oxaliplatin – an akylating agent

- Irinotecan – a topoisomerase inhibitors

Chemotherapy drugs target cells at different phases of the cell growth and replication cycle. Due to the differences in which cell cycle they impact, chemotherapy drugs are often used in combination and administered in a setting regimen (schedule) that aligns with this cycle. This regimen is typically repeated over a series of 3 to 6 months with a recovery period in between each regimen.

Some common treatment regimens using the above include:

- 5-FU alone

- 5-FU with leucovorin (folinic acid)

- Capecitabine alone

- Irinotecan alone

- FOLFOX: 5-FU with leucovorin and oxaliplatin

- FOLFIRI: 5-FU with leucovorin and irinotecan

- FOLFOXIRI: 5-FU with leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan

- XELOX/CAPEOX: Capecitabine with oxaliplatin

- Additional regimens also include the addition of targeted therapies (see below)

Progression free survival (PFS) or median survival has been shown to be similar whether FOLFIRI or FOLFOX regimens were used as initial therapy with the other used after progression of the disease. Median survival for patients with advanced colorectal cancer has also been shown to improve with the use of 5-FU plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan as a part of a treatment regimen over time with the order of the drugs given not impacts survival.

The above regimens are often altered with differing regimens prescribed if a patient has not achieved a tumor response or is deemed to have progressive disease, or if they begin to develop side effects to one or more of the drugs. Rechallenging a patient with a therapy is an option for patients whose initial therapy was stopped due to toxicity, a treatment break or patient preference, but not for retreatment in patients whose disease progressed following the use of the regimen.

Side effects of chemotherapy

Unfortunately, since chemotherapy drugs work at on all cells that grow quickly, other cells besides cancer cells which also have rapid growth can be affected. This includes cells lining the gastrointestinal tract, hair follicles and bone marrow cells. As a result, side effects like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, and low red and white blood cell and platelet counts, The latter can lead to anemia and fatigue, bleeding and bruising, and infections. Major hair loss is not common with most of the drugs used to treat colorectal cancer, except irinotecan. These side effects are often dose dependent and are often alleviated when the drugs are discontinued.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or biologics that targets specific genes, proteins, or other factors that have a role in the growth of cancerous cells. Since chemotherapy drugs affects all cells that multiply quickly, this results in possible side effects since these drugs also affect healthy cells which divide quickly like those in the bone marrow, stomach, mouth and hair follicles. Targeted therapies work differently and typically have less sided effects since they have the reduced potential to cause damage to healthy cells.

Since targeted therapies require specific biologic conditions to work, not all patients with colorectal cancer may be candidates for these drugs. Some therapies are depending on the patient having specific genetic attributes, proteins or other factors in order to work. Targeted therapy can be used as neoadjuvant therapy to reduce the size of the tumor prior to surgery, as adjuvant therapy to eliminate any remaining cancer cells and minimize the risk of disease recurrence, to treat cancers that do not responded to initial treatments or reoccurs, and as maintenance therapy to prevent the cancer from returning.

Types of target therapy

Currently, the two main types of drugs used for targeted therapy are monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors. This includes:

Monoclonal antibodies – synthetically produced versions of natural antibodies that bind with a protein on the surface of cancer cells or the surrounding tissues which impact the how cancer cells grow and survive.

Small molecule inhibitors – drugs which can enter cancer cells and block specific proteins which are needed for cancer cells to grow.

The following are examples of types of targeted therapies which are sometimes used to treat colorectal cancer:

- Anti-angiogenesis therapies – these drug block vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that is produced to help tumors form new blood vessels (angiogenesis) in order to get the nutrients they need to grow.

Examples include

– Bevacizumab

– Ramucirumab

– Ziv-aflibercept

The above are administered intravenously every 2 or 3 weeks, often in combination with chemotherapy.

- Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors – The surface of cancer cells can sometimes have high EGFR levels which increases the ability for these cells to grow and divided through the activation of tyrosine kinase activity. EGFR inhibitors block this receptor on the cell surface.

Examples include

– Cetuximab

– Panitumumab

The above are administered intravenously every week or every other week.

Since both drugs are not as effective for tumors which have specific mutations in RAS (KRAS and NRAS) or BRAF genes, it is important that the patient’s tumor is tested for these mutations prior to initiating therapy. The exception to the above is when cetuximab is used in combination with the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib (see below). These two drugs combined have been shown to effective in treating some patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumor expresses a BRAF V600E mutation.

- BRAF inhibitors – the BRAF gene makes a protein that is involved in cell signal and growth. Tumors which have a mutated version of the BRAF V600E gene have an increased growth rate and spread of cancer cells. Less than 10% of tumors from patients with colorectal cancer have this mutation. A combination of the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib and cetuximab has been shown to improve outcomes in some patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who have the BRAF V600E mutation. Encorafenib is given orally once daily when used in combination with cetuximab.

- Kinase inhbitors – Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusions result in the production of an abnormal protein (TRK fusion proteins) which can cause cancer cells to grow. While rare, this type of genetic change is found in a number of cancers, including colorectal cancer. Larotrectinib is the only kinase inhibitor that currently has FDA approved for use in patients with colorectal cancer. It is indicated for use in patients with solid tumors that have NTRK gene fusion, have metastatic disease or where surgical resection is not recommended, and have progressed following treatment or have no satisfactory alternative therapy.

Immunotherapy

A newer approach to treating cancer is the use of immunotherapy. This approach leverages the body’s immune system to augment its ability to detect and destroy cancer cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are the currently the only type of immunotherapy that is currently approved for the treatment of colorectal cancer. These drugs turn on an individual’s immune system to attack tumors.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Studies have shown that checkpoint inhibitors work best in patients who have certain genetic changes such as a high level of microsatellite instability (MSI). MSIs are regions of repeated DNA bases (microsatellites) when mismatch repair is not working properly or there are defects in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes.

Mismatch repair (MMR) deficient cells usually have many DNA mutations, which may lead to cancer. This is most often found in patients with colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, and endometrial cancer, but can also be found in many other types of cancer. Knowing whether a cancer has microsatellite instability can help identify potential treatment options.

There are currently two class of checkpoint inhibitors. This includes:

- PD-1 inhibitors

Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are drugs that target PD-1, a specific protein on T cells that keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against cancer cells. Pembrolizumab is indicated for first line treatment in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. It is administered via intravenous infusion every 3 or 6 weeks. Nivolumab is used alone or in combination with ipilimumab (see below) for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer that has progress after treatment with chemotherapy. It is also administered as an intravenous infusion every 2 or 4 weeks when given alone or every 3 weeks if given in combination with ipilimumab.

- CTLA-4 inhibitor

Ipilimumab works by blocks CTLA-4, is a protein receptor on T cells that functions as an immune checkpoint and downregulates immune responses. It can be used alone or in combination with nivolumab to treat colorectal cancer, d alone. It is also administered as an intravenous infusion every 3 weeks for 4 treatments.

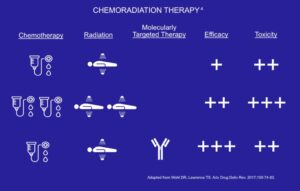

Chemoradiation therapy

Sometimes chemotherapy is used in conjunction with radiation in the above settings.

CRT has also been used to shrink tumors when given in a neoadjuvant setting, increasing the possibility of enabling curative surgical interventions in patient’s tumors previously deemed unresectable.3 With the availability of newer immunotherapy drugs including immune checkpoint inhibitors, the combination of these agents with radiation is an increasing area for research.4

- Qaderi SM, Galjart B, Verhoef C, Slooter GD, Koopman M, Verhoeven RHA, de Wilt JHW, van Erning FN. Disease recurrence after colorectal cancer surgery in the modern era: a population-based study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Nov;36(11):2399-2410. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-03914-w.

- Vogel JD, Felder SI, Bhama AR, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022 Feb 1;65(2):148-177. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002323.

- Rallis KS, Lai Yau TH, Sideris M. Chemoradiotherapy in Cancer Treatment: Rationale and Clinical Applications. Anticancer Res. 2021 Jan;41(1):1-7. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14746.

- Wahl DR, Lawrence TS. Integrating chemoradiation and molecularly targeted therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017 Jan 15;109:74-83. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.007.